The following article has been submitted to GPAC by Chkoun? Collective on the increasing use of arbitrary imprisonment as a weapon of state repression by the authoritarian and anti-migrant Tunisian state.

20/11/2024

**French translation below**

**Mobilize for the immediate release of the Tunisian Black feminist activist Saadia Mosbah and all those detained for solidarity with migrants! Mobilize for an end to the violence against Black migrants and refugees in Tunisia!**

Dear comrades,

We reach out to you with a piece of news wildly overlooked in the media, and a call to action.

Saadia Mosbah, a brave Tunisian Black feminist and steadfast advocate for racial justice in Tunisia, has been unjustly imprisoned for her activism on May 6th 2024. Saadia, a relentless defender of Black Tunisians’ rights and a leading figure in combating anti-Black racism and injustice more widely, is being targeted for her commitment to freedom and equality. She is the president of M’nemty, an association that has tirelessly fought to challenge systemic racism and advocate for racial justice in Tunisia, and has secured many achievements since the 2011 revolution.

Tunisian authorities have detained Saadia on unfounded money laundering charges, detaining her for nearly seven months without any evidence. They continue to hold her in custody while searching for proof to justify the charges, effectively normalizing the practice of “imprison now, prove later,” a blatant violation of justice and due process.

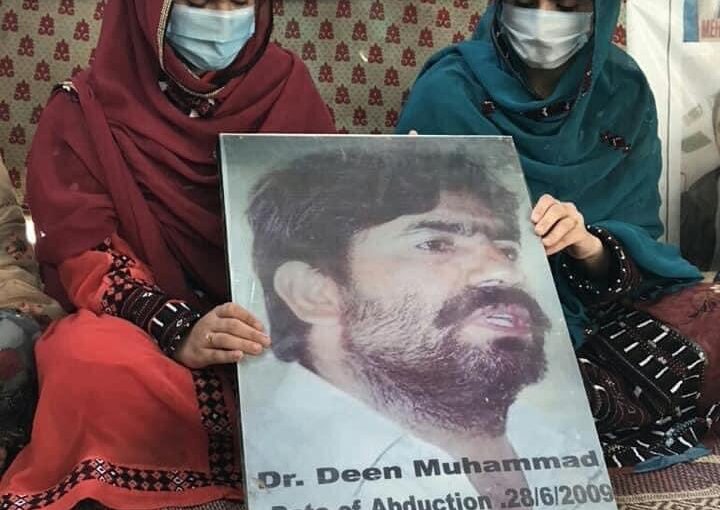

Saadia’s arrest must be understood as part of a wider attempt to silence and punish those who resist state repression. Her treatment has been riddled with anti-Blackness and misogyny, aimed not only censoring her but also at sending a message to all Black, feminist and minoritized groups across Tunisia. Many individuals have already been arrested for taking position against racism. Among them are Cherifa Riahi, targeted for her work with a migration solidarity NGO; Sonia Dahmani, detained for speaking out against state and societal racism on a radio show; Rachid Tamboura, detained for a graffiti tag criticizing President Kais Saied and more recently Abdallah Said, Black Tunisian activist and president of the “association Enfants de la Lune” in Médenine detained with charges of assisting migrants in Médenine. Many others remain behind bars with cases receiving little to no media attention. These arrests bring the criminalization of solidarity to a whole new level.

This is unfolding in a political climate fueled by fascist groups spreading conspiracy theories, amplified by a state apparatus rooted in xenophobic nationalism and authoritarianism. Tunisian authorities have been carrying out illegal deportations, abandoning Black migrants and refugees in desert areas where they are left to die from thirst and hunger, and isolating thousands others in remote camps where they face immense violence and discrimination, and lack access to basic services. Numerous recent reports reveal that these brutal actions are knowingly financed by the EU, as part of its strategy to externalize its borders to Tunisia and neighboring countries.

It is critical that we show solidarity with Saadia Mosbah and amplify her struggle internationally and the struggles of all those jailed for their principled stances for justice in Tunisia. We urge Black feminists, prison abolitionists, and comrades around the world to mobilize. We must highlight the connections between Saadia’s case and the broader pattern of racialized, patriarchal repression that many Black and anti-racist organizers face worldwide.

**Here’s how you can help:**

1. **Spread Awareness**: Share Saadia’s story across social media, in newsletters, and within community spaces. Expose the Tunisian authorities’ anti-Black and patriarchal practices.

2. **Call for an end of this injustice**: Contact international organizations and your local representatives and demand pressure on Tunisian authorities and statements condemning this injustice.

3. **Support M’nemty and other anti-racist and migrant and refugee organizations**: Show support towards Saadia’s organization, M’nemty, which continues to face harassment. Also follow the work of Refugees in Tunisia, Refugees in Libya, La Voix des Femmes Tunisiennes Noires and the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights, amplify their demands, and follow their recommendations to insure their safety.

4. **Organize and Demonstrate**: Mobilize protests, online and offline, to show solidarity with Saadia. Demand her immediate release and an end to the violent repression of activists in Tunisia.

Saadia Mosbah’s imprisonment is not an isolated event; it is a systemic attack against the Black feminist movement in Tunisia and a warning to all who oppose state oppression. By raising our voices together, we can help secure her release and affirm that the fight for racial and gender justice will not be silenced.

In solidarity and resistance,

Chkoun collective

Find our work and contact here: https://linktr.ee/chkoun_collective

Links with more information:

- Article on Jadaliya about Saadia’s arrest and the situation in Tunisia: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/46064/Saadia-Mosbah,-Black-Tunisian-activist,-arrested-on-6-May-2024

- Petition for the release of Saadia Mosbah https://www.change.org/p/call-for-the-immediate-release-of-saadia-mosbah-and-the-end-of-the-defamation-campaign

- Statement by Voice of Tunisian Black Women (in Arabic): https://www.facebook.com/VFTN20/posts/pfbid02wCR7ztLxJk9PrPL7QWRgDSxb8zice32YGYYPGDjzsea36ditvzcvH5LD8MJkp63ol

- Article on the arrest of Abdallah Said: https://www.infomigrants.net/fr/post/61258/tunisia-advocates-for-migrant-rights-held-in-antiterrorism-investigation

- Desert dumps – Lighthouse Reports: https://www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/desert-dumps/?utm_campaign=later-linkinbio-seawatchcrew&utm_content=later-43261346&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkin.bio

- Tunisia: Repressive crackdown on civil society organizations following months of escalating violence against migrants and refugees – Amnesty: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/05/tunisia-repressive-crackdown-on-civil-society-organizations-following-months-of-escalating-violence-against-migrants-and-refugees/

——————————————————————————————————————-

**Mobilisation pour la libération immédiate de la militante féministe Noire Tunisienne Saadia Mosbah et de toutes les personnes détenues pour solidarité avec les personnes migrantes ! Mobilisation pour la fin de la violence contre les personnes migrantes et les réfugié.es Noir.es en Tunisie!

Cher.es camarades,

Nous nous adressons à vous pour vous faire part d’une nouvelle négligée par les médias et pour vous lancer un appel à l’action. Saadia Mosbah, une courageuse féministe Noire tunisienne et une avocate indéfectible de la justice raciale en Tunisie, a été injustement emprisonnée pour son activisme le 6 mai 2024. Saadia, qui défend sans relâche les droits des Tunisien.nes noir.es, également, une figure de proue dans la lutte contre le racisme anti-Noir et l’injustice en général, est prise pour cible en raison de son engagement en faveur de la liberté et de l’égalité. Elle est présidente de M’nemty, une association qui s’est battue sans relâche contre le racisme systémique et pour la justice raciale en Tunisie, et qui a obtenu de nombreux résultats depuis la révolution de 2011.

Les autorités tunisiennes ont arrêté Saadia sur la base d’accusations infondées de blanchiment d’argent et l’ont détenue pendant près de sept mois sans aucune preuve. Les autorités continuent de la maintenir en détention tout en cherchant des preuves pour justifier les accusations, normalisant ainsi la pratique « emprisonner maintenant, prouver plus tard », ce qui constitue une violation flagrante de la justice et des droits de la défense.

L’arrestation de Saadia doit être comprise comme faisant partie d’une tentative plus large de réduire au silence et de punir ceux et celles qui résistent à la répression de l’État. Son traitement a été truffé de mesures anti-noires et de misogynie, visant non seulement à la censurer, mais aussi à envoyer un message à tous les groupes de Noirs, de féministes et de minorisés en Tunisie. De nombreuses personnes ont déjà été arrêtées pour avoir pris position contre le racisme. Parmi elles, Cherifa Riahi, ciblée pour son travail avec une ONG de solidarité avec les personnes migrantes ; Sonia Dahmani, détenue pour avoir dénoncé le racisme de l’État et de la société lors d’une émission de radio ; Rachid Tamboura, détenu pour un graffiti critiquant le président Kais Saied et, plus récemment, Abdallah Said, militant Noir tunisien et président de l’association « Enfants de la Lune » à Médenine, détenu pour avoir aidé des personnes migrantes à Médenine. De nombreuses autres personnes sont toujours derrière les barreaux et leurs cas ne reçoivent que peu ou pas d’attention de la part des médias. Ces arrestations portent la criminalisation de la solidarité à un tout autre niveau.

Tout cela se déroule dans un climat politique alimenté par des groupes fascistes qui diffusent des théories du complot, amplifié par un appareil d’État ancré dans le nationalisme xénophobe et l’autoritarisme. Les autorités tunisiennes procèdent à des expulsions illégales, abandonnent des personnes migrantes Noires et des réfugié.es dans des zones désertiques où iels meurent de soif et de faim. Les autorités Tunisiennes isolent des milliers d’autres dans des camps reculés où iels sont confronté.es à une violence et à une discrimination extrêmes et où iels n’ont pas accès aux services de base. De nombreux rapports récents révèlent que ces actions brutales sont sciemment financées par l’UE, dans le cadre de sa stratégie d’externalisation de ses frontières vers la Tunisie et les pays voisins.

Il est essentiel que nous soyons solidaires de Saadia Mosbah et que nous amplifiions sa lutte au niveau international, ainsi que les luttes de toutes les personnes emprisonnées pour leurs positions de principe en faveur de la justice en Tunisie. Nous exhortons les féministes Noires, les abolitionnistes de prison et les camarades du monde entier à se mobiliser. Nous devons mettre en évidence les liens entre le cas de Saadia et le modèle plus large de répression raciale et patriarcale auquel de nombreux.se organisateur.ices Noir.e.s et antiracistes sont confronté.e.s dans le monde entier.**Voici comment vous pouvez nous aider:**

1. **Sensibiliser** : Partager l’histoire de Saadia sur les médias sociaux, dans les bulletins d’information et dans les espaces communautaires. Exposer les pratiques patriarcales et anti- Noires des autorités tunisiennes.

2. **Appeler à mettre fin à cette injustice** : Contacter les organisations internationales et vos représentants locaux et exiger des pressions sur les autorités tunisiennes et des déclarations condamnant cette injustice.

3. **Soutenir M’nemty et d’autres organisations antiracistes, de migrant.es et de réfugié.es** : Apportez votre soutien à l’organisation de Saadia, M’nemty, qui continue d’être harcelée. Suivre le travail de “Réfugié.es en Tunisie”, “Réfugiés en Libye”, “La Voix des Femmes Tunisiennes Noires” et le “Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Sociaux et Economiques”, amplifier leurs revendications, et suivre leurs recommandations pour assurer leur sécurité.

4. **Organiser et manifester** : Mobilisez des manifestations, en ligne et hors ligne, pour montrer votre solidarité avec Saadia. Exiger sa libération immédiate et la fin de la répression violente des activistes en Tunisie.

L’emprisonnement de Saadia Mosbah n’est pas un événement isolé ; il s’agit d’une attaque systémique contre le mouvement féministe Noir en Tunisie et d’un avertissement pour tous celleux qui s’opposent à l’oppression de l’État. En élevant nos voix ensemble, nous pouvons contribuer à sa libération et affirmer que la lutte pour la justice raciale et de genre ne sera pas réduite au silence.

En solidarité et en résistance,

Le Collectif Chkoun

Découvrez notre travail et trouvez nos coordonnés ici: https://linktr.ee/chkoun_collective

Liens avec plus d’information:

- Article sur Jadaliya à propos de l’arrestation de Saadia’s et la situation en Tunisie: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/46064/Saadia-Mosbah,-Black-Tunisian-activist,-arrested-on-6-May-2024

- Petition pour la libération de Saadia Mosbah https://www.change.org/p/call-for-the-immediate-release-of-saadia-mosbah-and-the-end-of-the-defamation-campaign

- Communiqué par La Voix des Femmes Tunisiennes Noires (en Arabe): https://www.facebook.com/VFTN20/posts/pfbid02wCR7ztLxJk9PrPL7QWRgDSxb8zice32YGYYPGDjzsea36ditvzcvH5LD8MJkp63ol

- Article sur l’arrestation d’Abdallah Said : https://www.infomigrants.net/fr/post/61258/tunisia-advocates-for-migrant-rights-held-in-antiterrorism-investigation

- Desert dumps – Rapport de Lighthouse: https://www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/desert-dumps/?utm_campaign=later-linkinbio-seawatchcrew&utm_content=later-43261346&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkin.bio

- Tunisie: Répression des organisations de la société civile après des mois d’escalade de la violence à l’encontre des migrant.es et des réfugié.es – Amnesty: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/05/tunisia-repressive-crackdown-on-civil-society-organizations-following-months-of-escalating-violence-against-migrants-and-refugees/